I was visiting a friend in Harlem yesterday when I learned of Isaac Hayes’ death. The texts and emails came one right after the other. Like most of you, I was felt a pang in my heart. “Back to back! What does this mean?” I wondered. During this corridor last year (July and August), the community was also hit back-to-back with great losses: Sekou Sundiata, Mzee Moyo, Asa Hilliard, and Jon Lucien. This time, it was Bernie Mac and Isaac Hayes, during the same weekend. Dr. Barbara Ann Teer just three weeks ago. I’m not sure what our ancestors are trying to say to us with this rapid succession of death, but clearly they seek our attention.

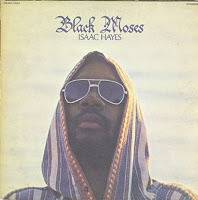

Besides loving those looooooooong, moody, soulful songs that Hayes gifted us, I loved the image of Black Moses. His image, coupled with the presence of my father in real life and John Amos as James Evans on Good Times, helped shaped my subconscious childhood definition of what a strong Black man was supposed to look like; how cool he was supposed to be.

Besides loving those looooooooong, moody, soulful songs that Hayes gifted us, I loved the image of Black Moses. His image, coupled with the presence of my father in real life and John Amos as James Evans on Good Times, helped shaped my subconscious childhood definition of what a strong Black man was supposed to look like; how cool he was supposed to be.

Read excerpt below or click HERE to read the full story (equals eight pages).

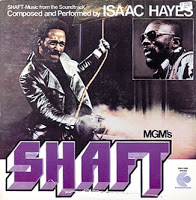

In the spring 2003, one year after his induction into the Rock and Roll Hall Of Fame and a celebrated move back home to Memphis, the public persona of Isaac Hayes is surging forward with a momentum usually associated with teen pop stars and visiting royalty. In fact, Hayes is resident royalty for more than a decade, a coroneted King of the Ada coastal district of Ghana in western Africa where he is a member of the Royal Family. Instead of a palace, he built an 8,000 square foot educational facility through his Isaac Hayes Foundation (IHF). He is most certainly the only King on earth with an Oscar, Grammy awards, #1 gold records, his voice on an animated TV series, a radio show, two restaurants, a best-selling cookbook, and top secret barbecue sauces.

In Memphis, his five-hour nightly radio shift on WRBO Soul Classics 103.5 FM is still the #1-rated show in town in its third year on the air. The city has taken to a new slogan: “Memphis: Home of the Blues, Birthplace Of Rock ‘n Roll,” underscored by the Smithsonian’s Memphis Rock ‘n Soul Museum just off Beale Street, the institution’s first permanent exhibition outside Washington, DC, and New York. On May 2nd, Hayes presided over the opening day ceremonies of Soulsville, the Stax Museum of American Soul Music, and a $20 million redevelopment project. It is located at a legendary address, 926 East McLemore Avenue, the revitalized original site of the record company where Hayes got his start in 1962. He has also been an integral fundraiser (and consciousness raiser) on behalf of the Stax Music Academy next door, a facility where he and others will develop and teach future Memphis musicians.

Soulsville

Isaac Hayes was born in the rural poverty of a sharecropper’s family on August 20, 1942, in Covington, Tennessee, about thirty miles south of Memphis. Orphaned in infancy, he and his sister Willette were raised up by their maternal grandparents, Willie and Rushia Addie-Mae Wade. They instilled love in Hayes for the simple pleasures of country life. “We raised our own foods,” he says, “we raised most of our crops, we had cattle, we had pork. Our corn was ground at the grist mill and we had molasses at the sorghum mill. A sack of flour would last several months. My grandmother did a lot of canning, preparing food and putting it up in the winter. My grandfather would go hunting and bring in a bunch of rabbits, so we were good. When we came to the city of Memphis, we didn’t have anything to compare it to.”Memphis was supposed to represent new opportunity, and it did for awhile, as the 7-year old saw his first supermarket and enjoyed his first Popsicle, and grandfather found work at a tomato factory. But soon his health failed, he became disabled, and when Hayes was 11, his grandfather died. “That’s when we really fell on hard times,” Hayes remembers, “when I started doing the agricultural work like picking cotton.” Ironically, his stately home today in East Memphis looks out on those same fields where cotton grew for nearly two centuries. As a youngster he ran errands, cut lawns, delivered groceries and wood to homes for fuel, cleaned bricks for two cents apiece, and shined shoes on Beale Street.

Later on, working as a bus boy and dishwasher at a restaurant, “one day it was kinda slow and I told the cook, ‘I been watching you, lemme do a hotdog.’ And he said, ‘ok, come on do it,’ so I prepared an artful hot dog, stuck it up in the window, tapped the bell and stepped back, watched the waitress deliver it, the guy ate it, and it was cool. I started doing some catfish, some hamburger steak, and the guy loved it. I eventually began doing a little short order cook stuff.”

To an adolescent, the poverty was stifling; combined with the self-consciousness brought on by puberty, believing he wasn’t dressed sharp enough to attract the girls, Hayes secretly dropped out of Manassas High School. After six weeks, a delegation of teachers arrived at the house and told his grandmother the news. “God, I felt like I had gone through the floor, but they said, ‘This young man has too much to offer, we cannot afford to lose him.'” The teachers gathered their hand-me-down clothes for Hayes, who resolved to stick it out and get his diploma. The experience left an indelible mark on him for life, and Hayes’ dedication to literacy, education and teaching initiatives is an outgrowth of what those teachers did for him. Years later, when the State Of Tennessee honored him with a marker, Hayes chose to place it at Manassas High.

Hayes sang in church since age five, but stopped when his voice cracked in adolescence. Years later, “when I started back singing, my voice was in the basement.” He was persuaded by his high school guidance counselor to enter a talent show, singing “Looking Back,” Nat King Cole’s 1958 hit. “When I finished, the house was on its feet, man, and I was a hit.” Overnight the girls, even those a couple of grades ahead, were sending lunch invitations. “Career change! So I started pursuing music big time.”

He joined the school band and learned to play saxophone from Lucian Coleman (brother of hard-bopper George Coleman). Hayes sang gospel with a group called the Morning Stars, doo-wop with Sir Isaac & the Doo-Dads, the Teen Tones, and the Ambassadors, even some jazz with the Ben Branch house band at Curry’s Club Tropicana out in north Memphis. He started playing sax and singing blues with Calvin Valentine and The Swing Cats, and doing prom dates with The Missiles. He took a crash course learning piano by literally faking it for the first time on a New Year’s Eve R&B job at the Southern Club with Jeb Stuart, “because I needed the money.”

Stax

Hayes was finally graduated at age 21 from Manassas, Class of 1962. It was the year after the first releases began to trickle out of a new label called Stax Records, part of the Satellite Records company and Satellite Record Store that started back in ’58, housed in the old Capitol Theatre on the corner of College & McLemore. Hayes had won seven college scholarships for vocal music that he chose not to pursue. Instead, he became adept enough at the piano to land a job with baritone saxophonist bandleader Floyd Newman at the Plantation Inn across the river in West Arkansas. Newman was also the staff baritone musician on Stax recording sessions and was up for a date himself with his own working group in late 1963: “Frog Stomp,” the only solo single ever cut by Newman, was co-written by and features Hayes (on piano), the first major notch in his discography at Stax Records.“During the time that I was there,” Hayes recalls of the session, ” Jim Stewart, the proprietor of Stax looked at me and said, ‘Look, Booker T is off in Indiana U., from Booker T & the MG’s, and I need a keyboard player so you want the job?’ ‘Yeaaa!’ I jumped at it.” His first paid sessions were with Otis Redding in early 1964, and Hayes was soon a ubiquitous presence at Stax. Not long after, co-writer and producer David Porter suggested to Hayes that they collaborate as songwriters. After a few modest starts for Porter (“Can’t See You When I Want To”), Carla Thomas “How Do You Quit [Someone You Love]”), and Sam & Dave (“I Take What I Want”), “everything just blew up big time,” Hayes says.

As writers (under the name ‘Soul Children’), arrangers and producers, the Hayes-Porter duo became Stax’s hottest commodity starting in 1966-67. Sam & Dave’s “You Don’t Know Like I Know,” “Hold On! I’m Comin’,” “Said I Wasn’t Gonna Tell Nobody,” “When Something Is Wrong With My Baby,” “I Thank You,” “Wrap It Up,” and the R&B Grammy award-winning “Soul Man” were among some 200 Hayes-Porter compositions that became standards. For Carla Thomas there was “Let Me Be Good To You,” “B-A-B-Y” and “Something Good (Is Going To Happen To You).” Johnnie Taylor scored with “I Had a Dream” and “I Got To Love Somebody’s Baby.” Mable John’s one and only hit was Hayes-Porter’s “Your Good Thing (Is About To End).” Presenting Isaac Hayes, his debut solo LP was recorded as a trio (with MG’s bassist Duck Dunn and drummer Al Jackson) in the wee hours after an all-night Stax party. The intimate, sensual jazz-flavored jam session approach (including three 9-minute versions of standards) did not reach the charts, but served as a blueprint for future LPs.

Hayes’ work with Sam & Dave, Otis Redding, Booker T & the MG’s, the Mar-Keys, the Bar-Kays, Rufus & Carla Thomas, and virtually the entire Stax roster created what was known as the Memphis Sound. It transformed popular music, was absorbed by everyone from Elvis Presley and Ray Charles to the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. History notes that, with the exception of Booker T & the MG’s, Isaac Hayes worked on more Stax sessions and tracks than any other musician.

On April 4, 1968, as Stax Records was finalizing its sale to Gulf & Western Corporation, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., was assassinated at the Lorraine Hotel in downtown Memphis. Hayes, who had marched for Civil Rights with King, was scheduled to meet with him that very day. “It affected me for a whole year,” Hayes told Rob Bowman in Soulsville U.S.A.: The Story Of Stax Records. “I could not create properly. I was so bitter and so angry. I thought, What can I do? Well, I can’t do a thing about it so let me become successful and powerful enough where I can have a voice to make a difference. So I went back to work and started writing again.”

Read the full bio at www.isaachayes.com.

Rest in Peace, Black Moses and may God keep his family, friends, colleagues during this difficult time.